Acknowledgements

This series is written with respect and gratitude for the W̱SÁNEĆ peoples – the MÁLEXEȽ (Malahat), W̱SĺḴEM (Tseycum), BOḰEĆEN (Pauquachin), SȾÁUTW̱ (Tsawout), and W̱JOȽEȽP (Tsartlip) – on whose land I currently live uninvited, for the lək̓ʷəŋən peoples – the Esquimalt and Songhees – on whose territory I study uninvited, and for the Hul’q’umi’num’-speaking peoples – the Halalt, Penelakut, Lyackson, Stz’uminus, Quw’utsun, Snuneymuxw, and Ts’uubaa-asatx Nations – on whose land I grew up. Their interconnectedness with the land and nature is a relationship that has existed since time immemorial and is one which continues to this day. I give respect to the Indigenous peoples, to the elders, and to the ancestors for their knowledge and wisdom that supports me as I am being educated and as I educate others.

Introduction

This blog post is one instalment of a two-part series on my free inquiry blog. So far on this blog, I have largely discussed websites and tools made by North Americans and Europeans. It is my responsibility – and my pleasure – as a future educator to acknowledge and promote resources created by Indigenous people in this series. As I write on these resources, I am consistently referring to and recalling the First Peoples Principles of Learning, which actively help to guide my education and my teaching practice.

Native Land Digital

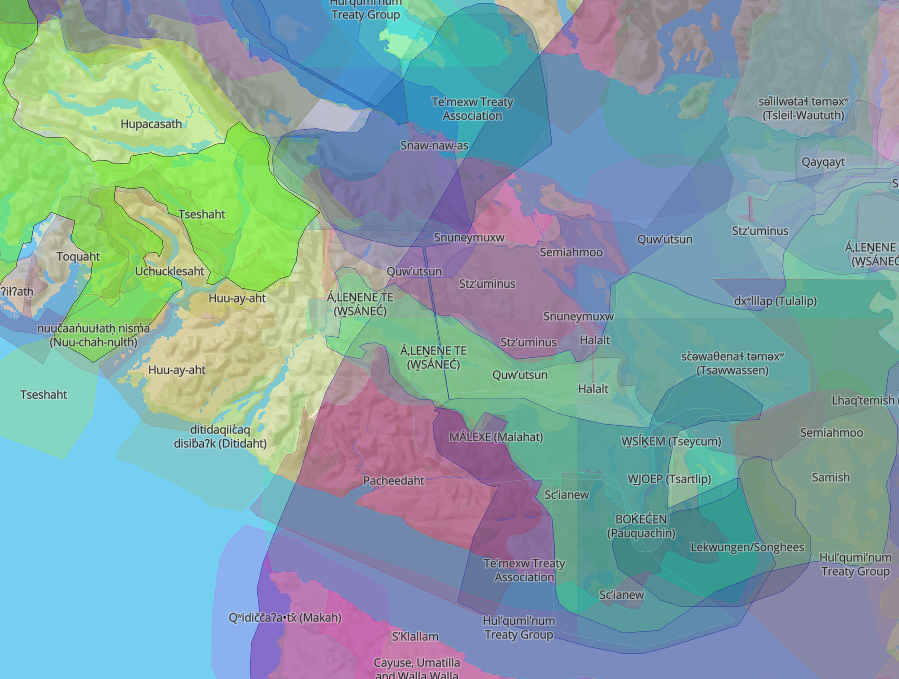

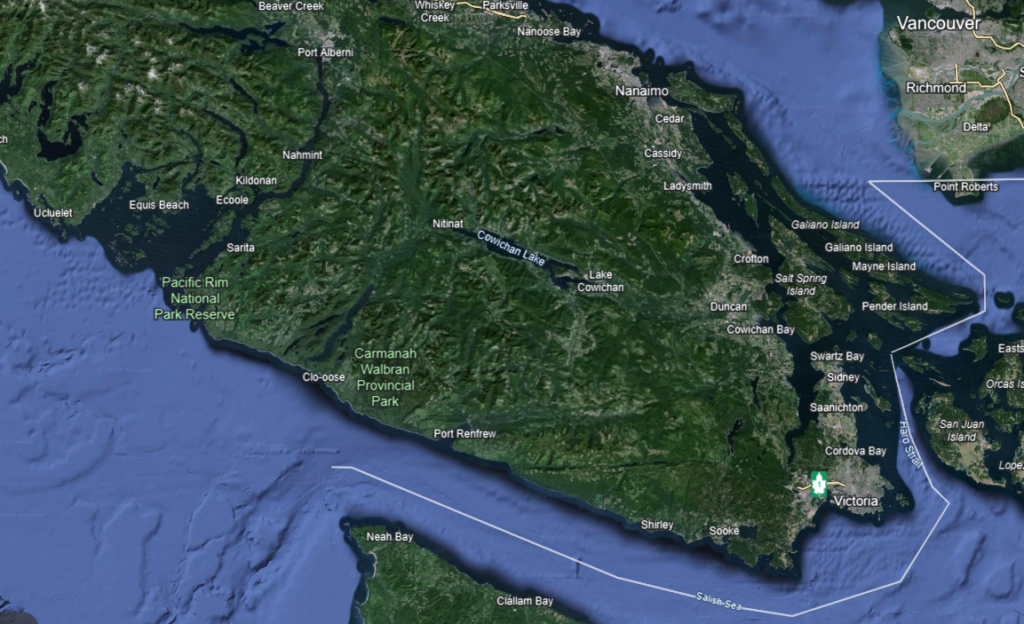

The second instalment in this series is on Native-Land.ca, which is an interactive map that is like a cross between Google Maps and Google Earth, but with a twist. Instead of showing borders, countries, states, or cities on the land masses of Earth, this map shows Indigenous peoples’ traditional territories, language groups, and treaties. This map is global, encompassing thousands of different peoples’ and nations’ land bases on almost every continent. Per their website, Native Land is “a Canadian not-for-profit organization, incorporated in December 2018.. is Indigenous-led, with an Indigenous Executive Director and majority Indigenous Board of Directors who oversee and direct the organization.” I have little to say that is not said in the description on the website, which essentially states that this project is one of massive importance because it reasserts in the digital world of the 21st century millenia-old Indigenous claims to territories which have only quite recently been stolen by Europeans all around the world, whose maps we now use to define the makeup of our planet. It provides an accessible, Indigenous repatriation of perspective on the land. This tool also provides a new perspective for non-Indigenous people with which to view the land we live on and the borders we usually draw on maps. As pictured below in both screenshots, the borders of each Indigenous nation or language group overlap almost everywhere on the southern part of Vancouver Island, BC.

Land is sacred, and those of us of European descent living here in Canada need a reminder of that; we do not live our lives as if it were true. We live as though land is something to be owned and utilized, not as a living being equal to us that we must protect as it protects us. The myriad Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island all share the belief in the sanctity of the land. Let us join them in viewing our land as something more than towns, roads, and resources.

How can teachers use this resource?

At its base, Native Land provides teachers and students – Indigenous or not – reliable and accessible information on whose traditional territory lies where. This may be in Canada or somewhere else in the world, but wherever you look there is extensive coverage of traditional territories and language groups backed up by Indigenous nations all over the world. Canada in particular has extensive, deep coverage on the website, which is a positive for teachers here. On Vancouver Island, the coverage is even more in-depth, which is due in no small part to the large level of diversity amongst Indigenous people here, as well as the strength of oral and written records that have been preserved for many generations.

Going past the informational aspect of the website, Native Land can also be used to compare and contrast the commonplace Google and/or Apple Maps that many of us are used to using. These maps are helpful in their own rights – especially when incorporated with Google Street View – but presenting them either alongside or at odds with the perspective of language groups or traditional territories can lead to some fascinating discussions and inquiries. An extension to this could even be to remake Google/Apple Maps in the style of Native Land using languages and traditional territories rather than strict borders with no depth. History and geography are told using maps, so instead of sticking to the 10 provinces and 3 territories of Canada or the 7 continents of the world, maybe we can recast our world with a historical perspective that shows respect to those who came before us and their relationships with their homelands.